Why the Dunning-Kruger Curves You’ve Seen Are Wrong

How a popular psychology hypothesis is being misrepresented online

Published on

Jun 14, 2021

Read time

3 min read

Introduction

From the media to the workplace, it’s easy to spot people with an overinflated sense of their own ability. This phenomenon is explained by the Dunning-Kruger effect, a hypothesis that people who are bad at a task or skill have a cognitive bias towards thinking they’re better than they are.

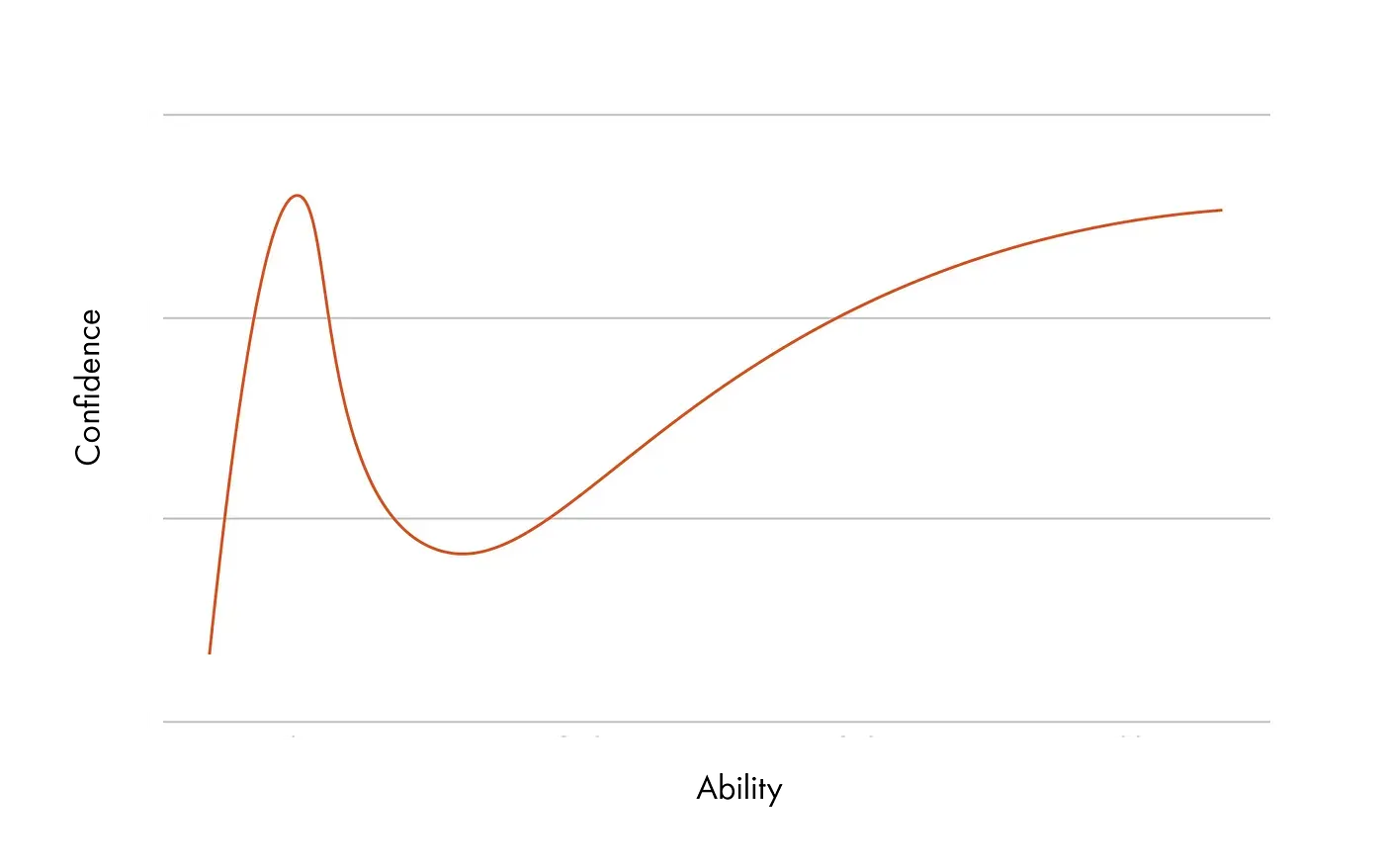

This is one of a handful of psychological concepts — alongside others like the Peter Principle and the Pareto Principle — which have become well-known among business circles online. However, a lot of online resources about the Dunning-Kruger effect are misleading. The worst offender is the so-called Dunning-Kruger curve, which is usually made to look something like this:

This curve implies that incompetent people think they’re better than competent people. It suggests that, after gaining a little ability in a skill, people vastly overestimate their confidence (the “Peak of Mount Stupid”) before realising they hugely underestimated the complexity of the skill (the “Valley of Despair”), and then steadily increasing in both confidence and expertise (the “Slope of Enlightenment”).

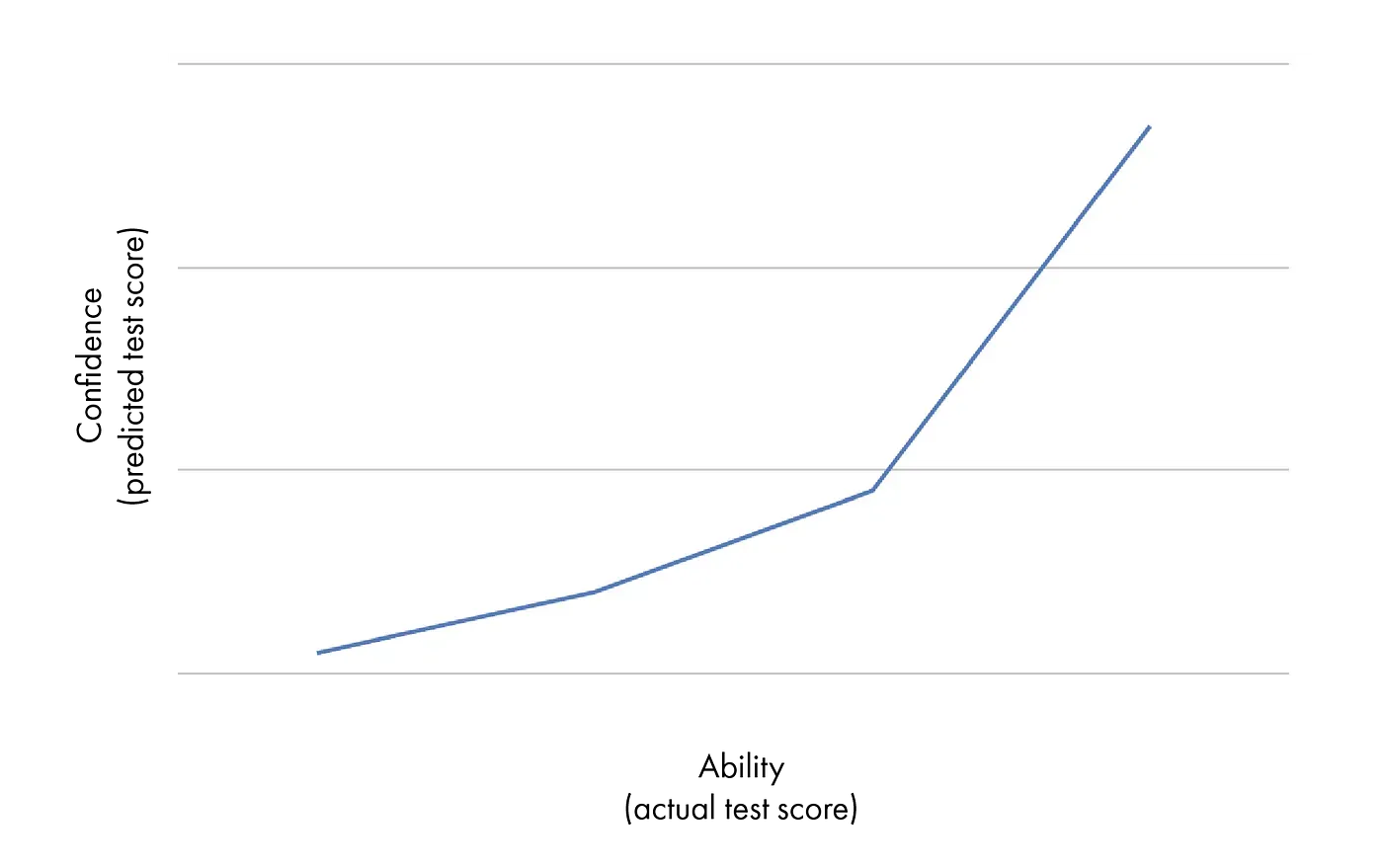

It’s a nice story, but it’s wrong. (Or at least, it misrepresents the actual Dunning-Kruger study.) If we were to plot confidence versus ability, based on the actual evidence, the graph would look something like this:

Without extra context, this curve in fact seems to contradict the core idea of the Dunning-Kruger effect!

The research actually suggests that, as a person’s ability increases, their confidence increases too. In fact, the better someone gets, the data suggests that their confidence grows even faster.

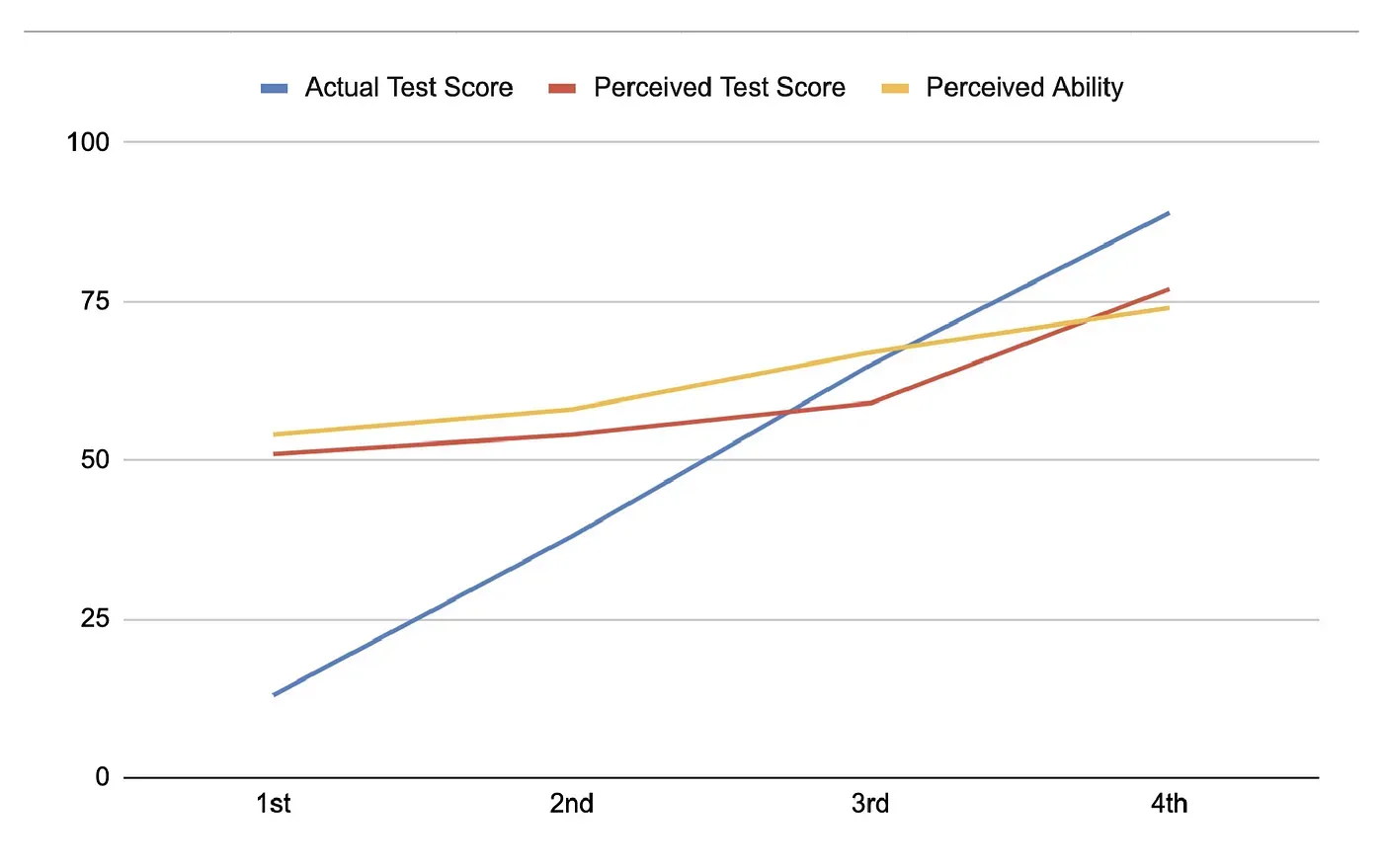

So what does the Dunning-Kruger effect actually describe? The chart below represents data from Study 4 in the original research paper. In the study, participants took a logical reasoning test. They were then asked to estimate:

- how many questions they answered correctly (the Perceived Test Score)

- their general logical reasoning ability, on a percentage scale, compared to the other participants (the Perceived Ability)

The participants were then split into quartiles from worst (1st quartile) to best (4th quartile). Here are the results:

This graph shows that the most competent people — those in the 4th quartile — do perceive themselves to be the best. Those in the 3rd quartile expected to do better than those in the 2nd quartile, who in turn expected to do better than those in the 1st quartile.

The most interesting part — and the reason Dunning-Kruger became popular in the first place — is the difference between perception and reality, represented by the gap between the blue line (Actual Test Score) and the red line (Perceived Test Score). Those at the bottom overestimated their ability to a much greater degree than anyone else.

The unskilled participants didn’t think they were better than the skilled participants; they just thought they would have scored better than they actually did! By contrast, the best half of the participants were more likely to underestimate their ability — a trend which gets more pronounced in the 4th quartile.

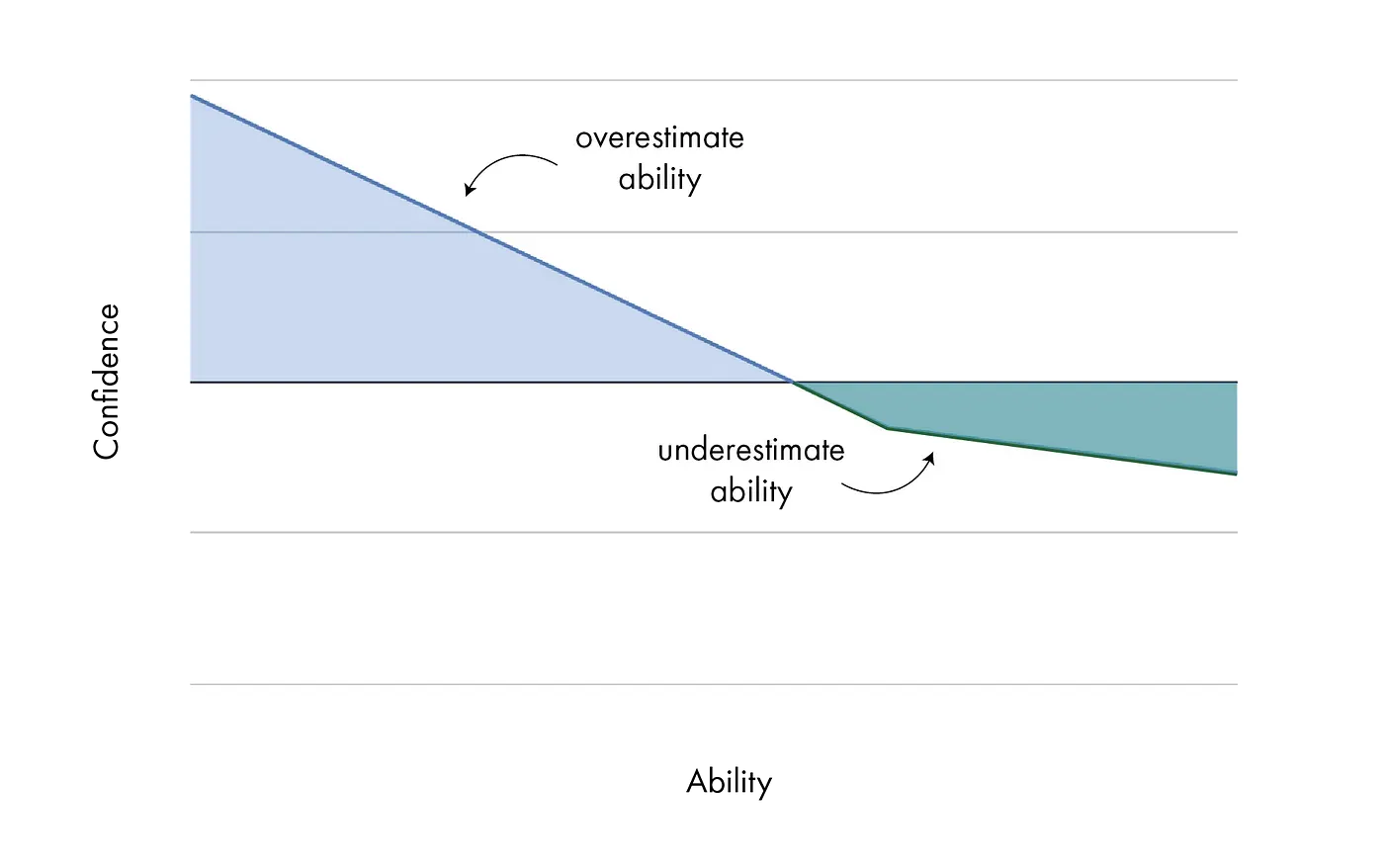

So, if we want to simplify the actual data above into a presentation-friendly Dunning-Kruger “curve”, I’d argue that this is a more accurate way of doing it:

Above, confidence is a measure of the difference been the predicted and the actual outcome. A score above zero means overconfidence: people thought they would do better than they actually did. A score below zero means the opposite: the participants did better than they predicted.

Finally, it’s important to be aware of the limitations of any research like this. The Dunning-Kruger study was relatively small, the largest study involved only 140 participants, most of a similar age and demographic — they were all psychology students at Cornell University. Since then, severl studies have been published suggesting the magnitude of the Dunning-Kruger effect may be less than previously reported.

In addition, subsequent studies have shown that culture can play a significant part in people’s overinflated sense of ability: in a similar study based in Japan, participants of all abilities were more likely to underestimate their skill level.

I’m also keen to cast doubt on the idea that overestimating your ability is unequivocally a bad thing, as terms like the “Peak of Mount Stupid” imply.

It’s possible that — when picking up a new skill — a degree of overconfidence could, in fact, be positive for the learner. The main reason is motivation: if you think you’re good at something, you may be more likely to stick with it, do it more often, and improve incrementally over time.

Related articles

You might also enjoy...

The State of AI Programming Going into 2026

Have LLMs become a mandatory programming tool?

4 min read

Dec 2025

Focus Doesn’t Scale

How to multitask when you’re wired for deep work

4 min read

Jul 2025

Are We Letting AI Code for Us — and Killing Our Skills?

The trade-off between mastery and speed

3 min read

Jun 2025